While the Western military tradition of training it's soldiers in the use of the bayonet might be presumed to be somewhat anachronistic there is a contemporary revival of it's practise. Surprisingly modern day bayonet fighting as a martial art owes it's preservation to the Japanese in the form known as Jūkendō.

A Last Hurrah for Cold Steel...

I found that I could not write a small piece on bayonet fighting without trying to find out when the weapon was last used in anger by the army. It's a hard piece of historical data to pin down really as there is a smattering of evidence of ad-hoc use of the bayonet as an offensive weapon right up to the UK's recent involvement in Afghanistan. (I will restrict myself to talking about the British Army in this context as the documentary information is easier to get hold of here.)

But, as for the kind of unit wide deployment of the bayonet is concerned - the kind we associate with the traditional sort of 'fix bayonets' action - the best known modern instance was when the Scots Guards took Mount Tumble down in the Falklands in 1982!

|

| Above: Scots Guards storm Argentine forces atop Tumbledown Mountain in the Falklands war, 4 June 1982, painting by Steve Noon |

Here's an article that covers historically recent 'bayonet charges' in more detail than I care to: 'Stickin’ It To ‘Em – The Last of the Great Bayonet Charges' By Military History Now.

Generally, though, it seems to be accepted that the bayonet - as a standard piece of equipment in the army - is disappearing or becoming more of a ceremonial item. One might say quite literally vanishing, in fact, as can be seen by the physical shrinking of the size of the weapon over the last century...

Practice Becomes Tradition Which Become Art

So, where is bayonet fighting today? A strange question you might think as we have already determined that militarily bayonet technique - as an intrinsic discipline taught to the soldier as a core skill - has gone (or is going) the way of the pike!

|

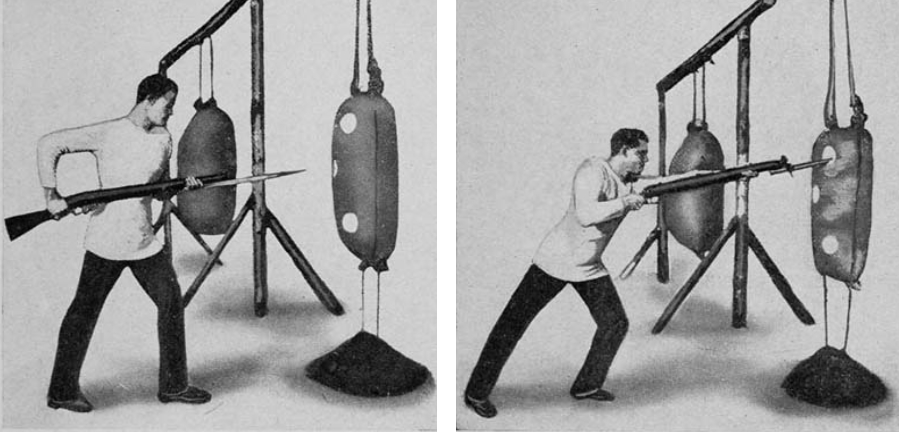

| Above: Plate from the 1917 British Army bayonet training manual, the 'long thrust'. |

Well, there are some who think that the preservation of 'obsolete' or 'outmoded' fighting techniques is important, despite the fact that the military themselves no longer perceive them as practical. These people might continue the practice of these techniques for reasons of practicality (self-defence) but also for reasons of tradition and/or additionally because these practices themselves have evolved into art forms. I am, of course, specifically talking about martial artists. (With a nod to reenactors, of course.)

Now I won't go into the very long explanation of the whys and wherefores of the plethora of disciplines that make up the umbrella term martial arts and the various reasons why people practice them. My sole focus here is how - today - some still practice bayonet fighting and who these people are.

It is in the land that has made an art of making art out of just about anything that we find our modern day proponents of bayonet fighting and that land is, of course, Japan!

Budō and Jūkendō.

Now, it is well known that militarily Japan has a long tradition of practicing bayonet fighting as a principal part of the martial philosophy that it calls Budō (or Bujutsu). In essence, and rather strangely, the bayonet and it's use was one of the very few Western fighting techniques that the Japanese considered to be worthy of assentation into the ranks of skills that were of a deeply spiritual worth.

|

| Above: Bayonet fighting is said to have been introduced to Japan by Shuhan Takashima (1798–1866) who adopted the techniques from Dutch sources (not French as some state). |

Budō (武道) is a rather difficult concept for the Western mind to grasp, particularly in how it can transition an act of violence and chaos - like bayonet fighting - into a practice that can be perceived as meditative or spiritual discipline. But, as I have said, the Japanese are consummately adept at turning anything into an art form.

Jūkendō (銃剣道) is the Japanese martial art of bayonet fighting, and has been likened to Kendō (to quote Wikipedia) and while pinching from that source I thing it's particularly fitting and relevant to additionally quote this passage from their entry on the meaning of Budō:

"Many consider budō a more civilian form of martial arts, as an interpretation or evolution of the older bujutsu, which they categorize as a more militaristic style or strategy. According to this distinction, the modern civilian art de-emphasizes practicality and effectiveness in favor of personal development from a fitness or spiritual perspective." Wikipedia.

This, for me, gives one a deeper understanding of the ART in MARTIAL ARTS. I have heard the term 'soft martial arts' used to describe certain disciplines that - for those who are looking primarily for a means of self-defence - are considered 'less effective' or 'merely choreography' (to paraphrase the critics). Arts like Tai-Chi are frequently referred to in this manner, even though - in it's beginning - it was developed as a practical fighting technique!

So, we see, there is a divergence of clear directly applicable purpose and a more philosophical, symbolic or spiritual path in some martial arts (not to forget sport and competition). Jūkendō is one of those disciplines which, like Kendō, is a descendent of a practical technique but which has evolved to be a 'way of' ( dō (道:どう) an ancestral skill - Kendō being the 'way of the sword' and Jūkendō being the 'way of the bayonet'; jūken 銃剣 meaning bayonet.

Here we see the 'way of' being a metaphorical or semi-symbolic representation of the original act used to define a deeper philosophical or culturally traditional meaning. For example, in the case of Kendō participants are preserving the traditional practice or ideal of Japanese sword fighting in a manner which is more symbolically representative and in a manner that is acceptable within a modern society that no longer sees the need to be carrying a sword. But I belabour the point... You get the idea.

The Way of the Bayonet

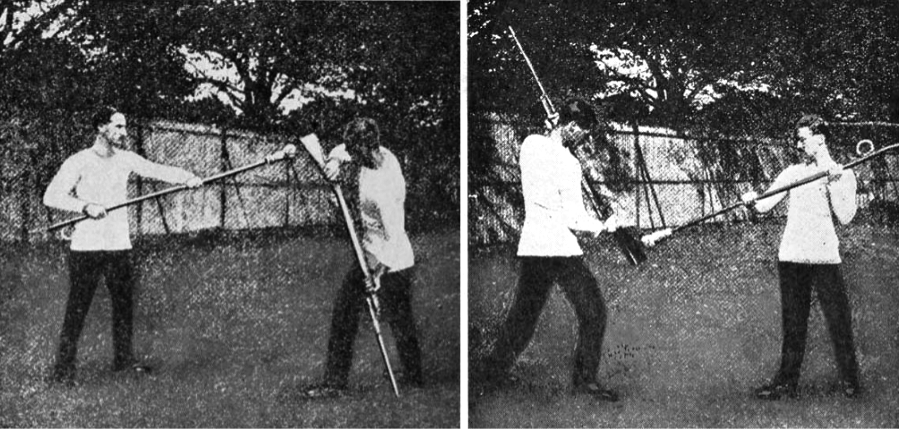

As with Kendō, it is quite obviously impractical for proponents of Jūkendō to have at each other with cold steel so they utilise what was originally a 'safe' training substitute for the real martial act in order to be able to participate in the Budō. Participating in the Budō is seen as a culturally important exercise connecting modern day proponents with their ancestral heritage, something that is intrinsic to Japanese society and their deeply held belief regarding ancestors and tradition.

You can get a sense of this spiritual aspect from how Japanese martial arts are strictly codified and conducted to the point where they almost become ritualistic.

In fact this is another criticism that is levelled at some Japanese martial arts by proponents of the more 'practical' or 'hard' self defence disciplines, that the ritual and etiquette of Budō influenced systems seems to attach as much importance to the way something is performed as much as the efficacy of technique itself.

"Beginning students in Japanese martial arts, such as karate, judo, aikido, iaido, kyudo, and kendo, learn that when they are in the dojo (the practice space), they must don their practice garb with ritual precision, address their teacher and senior students in a specific way, and follow certain unwritten but deeply held codes of behaviour." From 'In the Dojo: A Guide to the Rituals and Etiquette of the Japanese Martial Arts' By Dave Lowry

Indeed, I have seen examples of where that practise of Jūkendō (or even Karate) was actually mocked by other marital artists, in part because their form does not include any comparable philosophical aspect or because they cannot make the intellectual jump between the training with 'sticks' and how this practise has any bearing it a 'real world' application.

[This is an ongoing debate within the world of the martial arts, but it has always seemed to me that when we are talking about something as oddly superannuated as sword or bayonet fighting any debate about their 'practical effectiveness' as a form self-defence is somewhat moot, wouldn't you say? Factoid: The last documented sword duel in history was undertaken in France in 1967!*]

In the following video called 'Bayonet fencing training and drill' we see European exponents showing how - at one and the same time - bayonet fencing can be seen strangely idiosyncratic or quaint but, even so, it obviously still has the potentiality - even with blunted and sprung training arms - to be quite dangerous...

So we have a dichotomy. In it's surrogate (non-lethal training) forms modern bayonet fighting can be perceived as being rather eccentric, but - there again - common sense and safety dictates that in these 'symbolic' forms exponents are at the limits of what is logically circumspect.

In fact, ironically, we come full circle to that 1917 British Army training manual previously mentioned in this discussion. Here the practice of bayonet fighting 'with sticks' was seriously considered a viable mode of training even by a jingoistic and bullish military of the time...

They Don't Like It Up 'Em

You'll have to forgive me if I conclude this little look at such a niche martial art in such a frivolous manner, but even as someone who has become enamoured with the practise of Jūkendō I can - perhaps because I am British - see something slightly humorous in the very idea of fighting with 'sticks'. (I am a Monty Python fans so maybe that has something to do with it.)

To me, it is even more even more whimsical when one remembers that there was time in our recent history when 'fighting with sticks' was a very real and completely earnest idea. A situation which, superficially, seems like a sketch right out of the comedy 'Dad's Army' but which, at the time, had deadly serious reasons for being the way it was.

|

| Above: Top - a 1940 vintage British Home Guard Substitute Training Rifle. Bottom - Modern Japanese wooden 'Mokuju' Bayonet fighting rifle. |

But, on a more serious note, you might still be wondering what real use is a substitute wooden weapon compared to training with it's real counterpart? Well, aside from concerns over safety - which I have already mentioned - there is the elementary familiarity with basic handling drill which every novice should correctly learn before one comes to advanced martial concepts. This notion is as old as the inception of weapons themselves and, in fact, there is a name for this sort of wooden training weapon - a 'waster' (I kid you not)!

"Wasters are used to learn, practice, and later spar with a variety of techniques including cuts, slices, thrusts and wards...As the individual becomes more skilled, they will begin to use blunt steel weapons which offer a more realistic set of properties..." Wikipedia.

This idea - of transitioning from proxy weapons to the real thing - was noted in the British Army's 1917 Bayonet Training Manual...

"Progression in bayonet training is regulated by obtaining: first, correct positions and good direction; then, quickness. Strength is the outcome of continual practice."

And - importantly - the manual points out perhaps the most important goal of repetitive surrogate weapons training...

"An important point to be kept in mind in bayonet training is the development of the individual by teaching him to think and act for himself. The simplest means of attaining this is to make men use their brains and eyes to the fullest extent by carrying out the practices, so far as possible, without words of command. This procedure develops individuality and confidence."

And isn't individuality and confidence what many seek when they choose to take up a martial art?

____________________

References & Links:

> British Forces Bayonet Training Manual, 1917: www.gutenberg.org

> 'Home Guard Training Rifles' By David G. P Morse

> 'The last sword duel in history, France, 1967': RareHistoricalPhotos.com

> 'The Origins of Jukendo: Bayonet Combat in Japan': www.koryu.london

Post a Comment